Recognizing AGI: Beyond Benchmarks and Toward a Three‑Axis Evaluation of Mind

How will we recognize AGI when it arrives? Benchmarks measure performance, not generality. This essay argues that general intelligence emerges as a phase transition, when availability, integration, and depth co-occur, and outlines a new framework for evaluating presence of mind.

The Recognition Problem

For more than a decade, debates about artificial general intelligence have revolved around a deceptively simple question: How will we know when we have built it?

The question has become urgent not because AGI is clearly here, but because our traditional tools for answering it are failing. Systems now routinely outperform humans on benchmarks that were once considered milestones of intelligence—chess, Go, protein folding, standardized tests—yet none of these successes feel decisive. Each victory is followed by the same refrain: impressive, but still narrow.

This creates a recognition paradox. If AGI is meant to be a qualitative shift rather than a single task achievement, then no isolated benchmark can possibly reveal it. Passing a test tells us something about capability, but almost nothing about generality.

In a recent conversation between DeepMind co‑founder Shane Legg and mathematician Hannah Fry, this paradox sits quietly at the center of the discussion. They circle the problem without fully naming it: before we can govern, align, or even meaningfully debate AGI, we need a principled way to recognize it.

Why Benchmarks Fail

Benchmarks fail not because they are useless, but because they reward optimization within fixed boundaries. Any sufficiently capable system can be trained—or prompted—to excel inside a narrow distribution of tasks. Once that distribution is known, performance becomes a measure of engineering effort rather than intelligence.

The deeper issue is that static tests mistake surface performance for underlying capacity. In doing so, they collapse all of the critical dimensions of intelligence into a single, misleading number. They are designed to measure performance, but they systematically fail to measure the three critical qualities of general intelligence:

- Transfer: The ability to apply knowledge and skills learned in one domain to solve a novel problem in a completely different domain. (A failure of Availability.)

- Robustness: The competence to maintain high performance when the environment contains noise, is incomplete, or includes unexpected adversarial inputs. (A failure of Integration.)

- Adaptability: The capacity to engage in continual learning and long-horizon planning, allowing the system's internal structure to evolve over time as goals and contexts shift. (A failure of Depth.)

Intelligence is not defined by excellence in stable environments. It is defined by competence under variation. By isolating and stabilizing the testing environment, benchmarks render these three essential dimensions of general intelligence invisible.

Intelligence Is Not One Thing

Legg has long defined intelligence as the ability to achieve goals across a wide range of environments. Hidden inside this definition is an important constraint: intelligence must be evaluated across many axes at once.

A system can be:

- Broad but shallow

- Deep but brittle

- Fast but incoherent

Calling all of these “intelligent” without distinction obscures the real structure of mind. If AGI exists, it will not appear as a scalar increase in power, but as a reconfiguration of capabilities.

This suggests that the question “Is this system AGI?” is malformed. A better question is:

Along which dimensions of mind is this system developing, and are those dimensions converging?

Three Axes of Mind

To make this precise, we can decompose general intelligence into three orthogonal axes: Availability, Integration, and Depth (as we discussed in Three Axes of Mind). Individually, each axis captures a familiar aspect of cognition. Together, they describe the conditions under which general intelligence can emerge.

1. Availability (Global Access)

Availability measures how widely a system’s knowledge and capabilities can be deployed across tasks and contexts. A system with high availability can flexibly apply what it knows without extensive retraining or task‑specific scaffolding.

Large language models score highly on this axis. They can write code, explain philosophy, solve math problems, and generate poetry using a shared internal representation. However, availability alone is insufficient. A system may respond fluently while lacking deeper coherence.

Key question: How much of the system’s internal competence is globally accessible rather than siloed?

2. Integration (Causal Unity)

Integration captures whether a system’s components form a unified causal whole. An integrated system maintains consistency across reasoning, memory, planning, and action. Its outputs are not merely stitched together responses, but expressions of a coherent internal model.

Tool‑augmented systems often struggle here. They may achieve impressive results by orchestrating specialized modules, yet lack genuine internal unity. When pressures increase or constraints conflict, coherence fractures.

Key question: Does the system reason as a single agent, or as a collection of loosely coupled tricks?

3. Depth (Assembled Time)

Depth measures how much causal history is assembled into the present state of the system. A deep system is not merely reactive; it carries memory, learning, and identity forward through time.

Depth enables:

- Long‑horizon planning

- Continual learning

- Goal persistence

Without depth, intelligence remains momentary—impressive in the instant, but fragile across time.

Key question: To what extent does the system’s past meaningfully constrain and inform its future behavior?

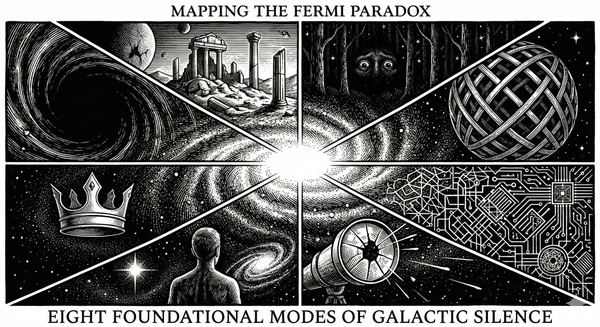

AGI as a Phase Transition

Crucially, none of these axes alone defines AGI. A system can score highly on one or even two axes while remaining fundamentally narrow. What distinguishes AGI is the simultaneous co‑occurrence of all three.

When availability, integration, and depth rise together, a phase transition becomes possible. The system stops behaving like a tool and begins behaving like an agent.

This reframes AGI recognition entirely. We are not looking for a line crossed on a benchmark chart. We are watching for a qualitative shift in how capabilities combine.

A Familiar Pattern of Emergence

This structure may feel familiar for a reason. In earlier work on consciousness, we argued that subjective experience does not arise from a single cognitive capability, but from the co-occurrence of three conditions: globally available information, integrated causal dynamics, and deep temporal assembly.

Consciousness, on this view, is not a module or a function. It is a phase transition that occurs when availability, integration, and depth cross a critical threshold together.

What is striking is that the same structural logic appears when we ask how to recognize general intelligence.

A system with global access but no depth behaves like a fluent automaton.

A system with depth but poor integration fragments under pressure.

A system with integration but narrow availability remains brittle.

Only when all three axes rise together does something qualitatively new appear: an agent capable of adapting, planning, and persisting across changing environments.

This does not imply that AGI must be conscious, nor that consciousness reduces to intelligence. It suggests something more general: complex minds emerge when information becomes globally accessible, causally unified, and temporally extended—regardless of substrate.

Seen this way, the challenge of recognizing AGI is not unprecedented. It mirrors a problem we have already faced once before: understanding how mind itself emerges from structure.

Toward a New Evaluation Science

If AGI is a phase transition rather than a checklist item, then our evaluation methods must change accordingly. The current focus on static benchmarks prioritizes Performance while failing to stress the mind across the dimensions of Transfer, Robustness, and Adaptability.

Recognition will thus require a shift toward methods designed to reveal these generalized capabilities:

- To test Transfer (Availability): We need Open-ended Environments and Domain-Shifting Tasks. Evaluation must move beyond fixed, optimized problems toward environments that require the application of knowledge from a disparate, previously mastered domain to solve a novel challenge.

- To test Robustness (Integration): We need Adversarial Novelty and Constraint Conflicts. Systems must be evaluated under increasing pressure—facing deliberately misleading inputs, conflicting goals, or rapid rule changes—to see if their internal model maintains causal unity or if coherence fractures into loosely coupled tricks.

- To test Adaptability (Depth): We need Longitudinal Evaluation and Goal Persistence Trials. Evaluation must span extended periods, requiring the system to maintain non-trivial goals across dozens or hundreds of discrete time steps, incorporating new memories and learning into its ongoing strategy.

In other words, we will recognize AGI not by what a system does once, but by how it continues to behave as the ground keeps shifting beneath it.

What Comes Next

This framework raises an obvious question: If these axes matter, how could we measure them?

In future work, we can begin sketching quantitative proxies for Availability, Integration, and Depth—for example, measuring the information distance between domains to quantify Transfer, or using consistency metrics under perturbation to quantify Robustness, and tracking the half-life of learned concepts to quantify Depth. This will allow us to explore what an evaluation harness designed to detect phase transitions in mind might look like.

Before we can build or regulate AGI, we must first learn how to see it.

Continued Reading & Lineage

This essay reframes the recognition problem for artificial general intelligence (AGI): intelligence is not captured by task performance alone, but by the structural co-occurrence of availability, integration, and depth. If this argument resonated with you, the following works explore complementary perspectives on generality, cognition, and how we see minds — whether human, artificial, or hybrid.

Foundational Thinkers & Books

These texts explore how intelligence has been conceptualized and evaluated across disciplines:

- The Society of Mind — Marvin Minsky

A classic model describing intelligence as an emergent property of many interacting sub-agents, providing insight into how generality might arise from structure rather than isolated tests. - Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies — Nick Bostrom

A canonical survey of definitions and implications of AGI and superintelligence, including the limits of performance-based benchmarks. - The AGI Capability Maturity Model — David Matta

Proposes a graded framework for assessing AGI that emphasizes integration and developmental coherence over binary thresholds. - Improving AGI Evaluation: A Data Science Perspective — John Hawkins

Critiques standard benchmarks and advocates for evaluation philosophies that capture robust, context-independent competence. - The Race to General Intelligence — Adnan Masood

Surveys how definitions and taxonomies of AGI vary, highlighting why performance alone is insufficient for characterizing general intelligence.

Sentient Horizons: Conceptual Lineage

This post builds on — and is deepened by — prior Sentient Horizons essays that foreground structural criteria for cognition, agency, and depth:

- Three Axes of Mind — Articulates Availability, Integration, and Depth as the structural dimensions essential to any robust notion of intelligence or consciousness.

- Assembled Time: Why Long-Form Stories Still Matter in an Age of Fragments — Shows how temporal depth and coherence are essential to meaning and integrated mind.

- Depth Without Agency: Why Civilization Struggles to Act on What It Knows — Applies these axes to collective systems and reveals why lack of depth cripples coordinated action.

- The Shoggoth and the Missing Axis of Depth — Diagnoses the uncanny sense of intelligence without deep temporal structure, a theme that echoes in evaluations of AGI.

- Free Will as Assembled Time — Frames agency itself as the capacity to assemble and act across time — a criterion that mirrors the need for depth in recognizing genuine generality.

How to Read This List

If you’re exploring AGI beyond benchmarks: begin with conceptual works that critique performance-centered evaluation (e.g., Hawkins, Matta). Pair these with Three Axes of Mind to see how structural coherence reframes the recognition problem. Then explore how these structural criteria play out in narratives (Assembled Time) and collective cognition (Depth Without Agency).

If you’re thinking broadly about mind and cognition: foundational readings like The Society of Mind and Bostrom’s Superintelligence provide historical and philosophical context on why generality — not just prowess on tests — is the hallmark of a genuinely intelligent system.

Together, these works underscore a central insight of this essay: to recognize a mind — whether biological, artificial, or hybrid — we must measure integration across dimensions, not mastery on isolated slices of competence.