Scaling Our Theory of Mind: From Individual Consciousness to Civilizational Intelligence

If individual minds emerge from availability, integration, and depth, what happens when those same conditions appear at the scale of civilization? We argue that political decay may be better understood not as moral failure, but as a cognitive pathology of systems that begin to lose their memory.

For much of human history, the mind has been treated as a strictly individual phenomenon: something that happens inside a skull, bounded by skin, sustained by neurons. Even when we speak of “collective intelligence” or “group behavior,” we usually mean this metaphorically: many minds acting together, not a causal agent in its own right.

But what if that intuition is incomplete?

In previous essays on Sentient Horizons, we developed a framework for understanding minds not as fixed entities, but as emergent structures; patterns that arise when three conditions co-occur:

• availability (information is globally accessible within the system)

• integration (the system functions as a causally unified whole)

• depth (the present is shaped by accumulated history)

Consciousness, on this view, is not a substance or a spark. It is a phase transition.

The question now is unavoidable:

If this framework correctly describes how individual minds emerge, what happens when these same properties appear at larger scales?

The Limits of the Individual Frame

We are comfortable scaling intelligence downward from humans to animals, to insects, to simple adaptive systems. We are far less comfortable scaling it upward.

Yet many of the structures that shape our lives already operate at scales far beyond the individual:

- Languages that outlive their speakers

- Institutions that persist for centuries

- Scientific traditions that accumulate insight across generations

- Technologies that externalize memory and decision-making

These systems store information, integrate action, and act on timescales no single human can inhabit.

If consciousness depends on assembled time, then its enabling structures should become more visible, not less, as temporal depth increases.

Civilizations as Memory-Bearing Systems

A useful starting point is memory.

In individual minds, cognition depends on the ability to retain structure across time. Without memory, experience collapses into momentary reaction. Depth is not an optional feature of consciousness; it is a prerequisite.

Civilizations display a strikingly similar dependency.

They persist only insofar as they maintain durable forms of collective memory:

- laws encode lessons from prior failures

- archives preserve accumulated knowledge

- education transmits structure across generations

- rituals stabilize meaning beyond individual lifespans

When these memory structures erode, civilizations lose coherence. They repeat errors, fragment internally, and struggle to coordinate long-term action.

This does not imply that civilizations are conscious in the way humans are. But it does suggest something more modest, and more useful:

The same structural features that make individual minds possible also appear to govern whether large-scale human systems remain coherent over time.

From this perspective, institutions function less like arbitrary social constructs and more like memory-bearing mechanisms: enabling continuity, coordination, and adaptive response at scales no individual mind can manage alone.

Beyond Metaphor: When Do Cognitive Patterns Recur Across Scales?

At this point, a familiar objection arises: isn’t this just metaphorical thinking?

But the same objection once applied to individual minds. Neurons, after all, are not conscious. No single synapse “feels like something.” Consciousness emerges only when the system reaches sufficient availability, integration, and depth.

The lesson is uncomfortable but clear:

The organizing features associated with minds do not appear to depend strictly on biological boundaries.

They require organizational thresholds.

If a civilization:

- integrates information across vast populations,

- maintains continuity across centuries,

- and coordinates action in response to internal representations,

then the question is no longer whether it resembles a mind, but in what ways, and with what limitations.

Timescales Change Everything

One of the most profound differences between individual and civilizational cognition is temporal resolution.

Human minds operate on seconds, minutes, years. Civilizations operate on decades, centuries, millennia. Their “thoughts” are slow. Their decisions unfold across generations. Their errors take centuries to correct.

This difference explains why civilizational intelligence often feels invisible or nonexistent. We are looking for cognition at the wrong speed.

A mayfly might conclude that humans do not think.

Why This Matters Now

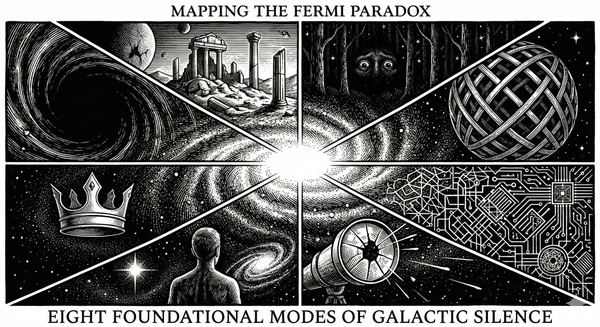

We are living through a moment when:

• information availability is accelerating,

• connectivity is increasing through global networks,

• but depth is eroding under speed and fragmentation.

So we appear to be increasing on two axes while starving the third.

But connectivity, unfortunately, is not the same as integration.

The internet connects us, but we are more polarized and fractured than ever. That isn't integration; that's just noise.

In this sense, many modern networks maximize information availability and connectivity while failing to cultivate the deeper forms of integration required for coherent action.

To further visualize how depth is eroding, contrast the "Archival Mind" (libraries, constitutions, 100-year plans) with the "Feed Mind" (algorithms that prioritize the last 5 minutes). Depth requires the past to weigh on the present; the "Feed" erases the past to maximize the present.

If civilizational behavior is examined through a cognitive lens, then many of our current failures, political instability, institutional decay, existential risk, begin to look less like moral shortcomings and more like cognitive pathologies.

A system that cannot remember cannot plan.

A system that cannot integrate cannot act coherently.

A system without depth cannot sustain meaning.

The Question Ahead

We do not yet have a blueprint for a civilization that solves these problems. But by reframing them as structural rather than moral, we can begin to imagine new architectures.

If individual consciousness emerges when availability, integration, and depth align, then civilizations may represent the next scale at which causal agency becomes possible, or collapses under its own complexity.

The question is no longer simply what is consciousness?

It is:

What kinds of worlds are capable of sustaining causal action over deep time?

To answer that, we have to zoom out: beyond individuals, beyond societies, and eventually beyond Earth itself.

The goal is not to engineer a singular planetary consciousness, but to ensure our civilizations possess the structural capacity to function. We need systems capable of compressing the past into causal agency: converting accumulated history into effective future action.

If we cannot solve this architectural problem on Earth, we will simply export our dysfunction to the stars. A Martian settlement that lacks this capacity, that cannot effectively bind its depth to its decisions, will not survive the indifference of space.

And that is where we go next.

Continued Reading & Lineage

This essay extends our Three Axes of Mind framework from individual minds into the domain of large-scale human systems, showing how availability, integration, and depth shape not only personal consciousness but the cognitive capacity of civilizations. To deepen your engagement with these ideas, the following works offer complementary theoretical, philosophical, and practical perspectives.

Foundational Thinkers & Books

These texts explore how cognition, intelligence, and collective structures emerge across scales and time:

- The Society of Mind — Marvin Minsky

A classic model treating mind as an emergent product of interacting simple “agents,” offering insight into how complexity and structure arise from many parts. - Thinking in Systems — Donella Meadows

A foundational introduction to systems thinking, feedback loops, and structural causes of stability and breakdown in complex systems. - Technics and Civilization — Lewis Mumford

Classic discussions on how technologies and institutions co-evolve with societal norms and cognition. - Figments of Reality — Jack Cohen & Ian Stewart

Explores recursion, emergence, and evolution of intelligence — useful for thinking about how complex systems encode and propagate information over time. - Collaborative Intelligence — Mira Lane and Arathi Sethumadhavan Illuminates how distributed systems can exhibit problem-solving capacities beyond the individual.

Sentient Horizons: Conceptual Lineage

This essay builds on — and is enriched by — earlier Sentient Horizons explorations into cognition, time, and structural depth:

- Three Axes of Mind — The foundational framework describing availability, integration, and depth as the structural axes of cognitive systems. Sentient Horizons

- The Universe as a Cognitive Filter — Situates cognition within broader cosmological and evolutionary constraints, showing how intelligence arises and is shaped by selective pressures on depth and continuity. Sentient Horizons

- Depth Without Agency — Shows how lack of depth corrupts collective action, helping explain why civilizations fail to act on what they know.

- The Shoggoth and the Missing Axis of Depth — Diagnoses the uncanny sense of intelligence without temporal depth, a theme echoed when collective systems lose memory and continuity.

- Free Will as Assembled Time — Provides a lens for understanding agency itself as the capacity to integrate deep temporal structure — a concept that scales into the collective domain when we ask how civilizations can act coherently across generations.

How to Read This List

If you’re interested in structural cognition across scales: begin with Three Axes of Mind to grasp the framework used here. Then read The Universe as a Cognitive Filter and Depth Without Agency to understand how depth shapes not just individual minds but the capacities and pathologies of larger systems.

If you’re drawn to collective intelligence and societal coherence: engage with systems-oriented and collective cognition literature (e.g., Minsky’s Society of Mind and Meadows’ work on systems) alongside the Sentient Horizons essays to see how patterns recur — whether inside a single brain or across centuries of civilizational memory.

Taken together, these works underscore a central insight of this essay: the structural features that enable individual minds — sustained memory, causal integration, and coherent access to information — also govern whether large-scale human systems can remember, unify, and act over deep time.