The Universe as a Cognitive Filter

Intelligence may be rare not because it is hard to create, but because it is hard to preserve. This essay reframes the universe as a cognitive filter—one that permits intelligence to arise, but places extreme pressure on its ability to persist.

Why Intelligence Is Rare, Fragile and Time-Bound

In our previous essay Scaling Our Theory of Mind: From Individual Consciousness to Civilizational Intelligence, we treated civilizations not as metaphors, but as real cognitive systems: entities that sense, remember, coordinate, and act across time.

This raises a deeper question — one that history, biology, and cosmology all quietly point toward.

If intelligence can emerge at the scale of a species or a civilization, why does it appear to be so rare in the universe? Why does it arise so late in cosmic history? And why, once it appears, does it so often fragment, collapse, or self-extinguish?

One place to begin looking for an answer is the historical record — and it is unambiguous:

Complex civilizations collapse, fragment, or radically transform far more often than they endure.

Examples are almost overwhelming in their abundance, spanning continents and millennia:

- Bronze Age collapse (~1200 BCE)

- The Western Roman Empire

- The Classic Maya

- The Indus Valley Civilization

- The Khmer Empire

- The Abbasid Caliphate

- The Aztec and Inca empires

- Imperial China’s repeated dynastic collapses

What’s striking is not that these societies lacked intelligence — many were technologically sophisticated, administratively complex, culturally rich, and in some cases astronomically knowledgeable.

Their failure mode was not ignorance, but the loss of integration and depth: institutional brittleness, elite fragmentation (a systemic failure in which competing factions dismantle shared mechanisms of coordination), breakdown of shared meaning, inability to adapt representations fast enough without losing coherence.

Intelligence clearly does not guarantee continuity.

The usual answers to this observation invoke probability, biology, or technological risk — suggesting that intelligence is unlikely to arise, difficult to sustain, or prone to catastrophic failure. But these explanations still tend to treat intelligence itself as the central achievement, rather than asking whether it can maintain integration and depth across deep time.

What if the universe doesn’t select for intelligence?

What if the universe instead functions as a cognitive filter — one that permits intelligence to arise, but places extreme pressure on its ability to persist?

Intelligence Appears Late Because Depth Takes Time

From the perspective of our framework, intelligence is not a single property. It emerges only when three conditions co-occur:

- Availability: information can access itself globally within a system

- Integration: components participate in a coherent, causally unified whole

- Depth: present behavior is shaped by deep, accumulated history

Availability can arise quickly. Integration takes longer. But depth is slow.

Depth is not a spark—it is sediment. It is the gradual layering of memory, structure, and meaning across immense spans of time. Before a system can think, it must first remember.

The universe spends billions of years doing this preparatory work:

- forging heavy elements in stellar furnaces,

- stabilizing long-lived stars,

- assembling planets with persistent energy gradients,

- allowing chemistry to complexify,

- and letting evolution ratchet forward without catastrophic interruption.

By the time intelligence appears, the universe is already old. Cooling. Expanding. Less forgiving.

Intelligence is therefore not early or inevitable. It is late, contingent, and fragile, arising only after long uninterrupted histories—and always under the shadow of eventual disruption.

Availability at Cosmic Scale Is Severely Constrained

At the scale of a brain or a planet, availability feels abundant. Signals propagate quickly. Feedback loops close. Information can become globally accessible within meaningful timeframes.

At cosmic scale, this collapses.

Physics imposes hard limits:

- Light speed constrains information flow

- Distance introduces delay and desynchronization

- Energy dissipates

- Matter decays

A civilization may be highly intelligent locally while remaining cognitively fragmented globally. As it spreads, availability does not scale smoothly—it fractures.

Space is not merely empty. It is anti-availability.

Signals arrive too late to matter. Coordination lags behind change. Shared context dissolves. The universe permits computation, but resists global access.

Integration Fails Under Distance and Expansion

Integration is not connectivity.

Connectivity is the ability to send a signal. Integration is the ability to maintain a shared reality.

A system can be densely connected yet poorly integrated—saturated with signals but lacking shared context, stable representations, or coordinated response. Integration requires not just links, but coherence across time.

At civilizational scale, integration is already difficult. At interstellar scale, it borders on impossible.

Distance breaks synchronization. Expansion dilutes causal unity. Subsystems drift into divergent contexts faster than feedback can reconcile them.

Expansion without integration is not growth—it is cognitive dilution.

This is not a speculative claim. We see it repeatedly:

- Empires fracture as they outgrow their ability to coordinate

- Institutions decay as their internal representations lose alignment

- Networks fragment when speed outruns shared meaning

The same structural failure that breaks an empire on Earth—the inability of the center to hold the periphery together—repeats at the cosmic scale, but enforced by the hard laws of physics rather than just bureaucracy.

The universe allows expansion, but punishes coherence.

Depth Is the True Bottleneck

If availability is constrained by physics and integration by distance, depth is constrained by entropy.

Depth depends on preserved memory:

- cultural knowledge

- institutional continuity

- intergenerational meaning

- long causal chains remaining intact

But the universe erodes memory relentlessly.

Catastrophes reset progress. Entropy degrades structure. Knowledge decays faster than it accumulates. Institutions collapse more easily than technologies advance.

This leads to a crucial asymmetry:

Intelligence can arise accidentally.

Depth must be defended deliberately.

A civilization can become intelligent by chance. It can remain deep only through sustained effort.

Depth Is Not Hypothetical — It Has Failed Repeatedly

The argument so far is abstract — but its consequences are not. This fragility of depth is not speculative. It is one of the most consistent patterns in human history.

Archaeology and history show that complex civilizations fracture, unravel, or disappear far more often than they persist. The Bronze Age collapse, the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the disappearance of the Indus Valley civilization, the collapse of the Classic Maya, the repeated dynastic cycles of Imperial China — these were not failures of intelligence. They were failures of continuity.

In many cases, technological sophistication peaked shortly before collapse. Administrative complexity increased. Cultural production flourished. What failed was not ingenuity, but the ability to preserve shared meaning, institutional memory, and coordinated response under stress.

Even when civilizations leave behind monuments and artifacts, they often fail to leave behind interpretable continuity. Scripts go undeciphered. Technologies are lost. Knowledge survives in fragments, stripped of context.

A civilization may leave evidence that it existed — and still lose itself.

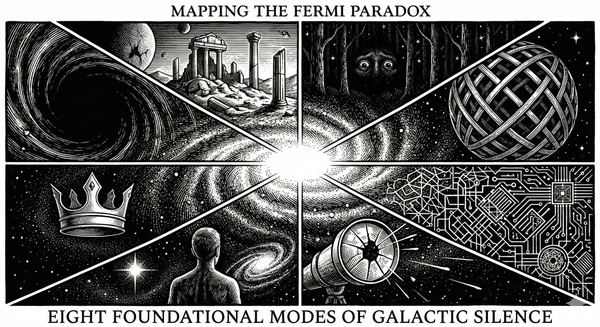

The Fermi Paradox Reframed

The classic formulation asks: Where is everyone?

But this question assumes that intelligence, once achieved, should naturally persist and expand.

Our framework suggests a different answer.

Civilizations do not vanish because they fail to think.

They vanish because they fail to continue.

They lose depth faster than they gain capability.

They fragment faster than they integrate.

They optimize speed over memory.

They expand availability without preserving meaning.

We see this same pattern even within a single, still-living civilization.

Modern institutions — governments, corporations, scientific bodies — routinely suffer from loss of institutional memory, mission drift, incentive misalignment, and short-term optimization that undermines long-term coherence. This occurs despite unprecedented connectivity, documentation, and computational power.

Availability has increased dramatically. Integration and depth have not kept pace.

This suggests that continuity failure is not a rare catastrophe, but a default tendency in complex systems. Intelligence accelerates capability faster than it preserves meaning. Coordination scales more slowly than complexity. Memory erodes unless actively defended.

The silence of the universe may not indicate a lack of beginnings. It may be a graveyard of broken continuities — civilizations that learned to think, but failed to remember.

Is the Universe Hostile to Intelligence?

No.

But it is profoundly indifferent to depth.

The universe readily supports:

- energy flow,

- computation,

- replication,

- local optimization.

It does not protect:

- memory,

- meaning,

- identity across time.

Anything that persists does so without help.

Depth survives only if systems actively maintain it.

The Pattern Persists Across Scales

This failure mode is not unique to human history.

Evolutionary history shows that intelligence arises late, rarely, and without guarantees of persistence. Most species that have ever existed are extinct. Highly intelligent hominins vanished despite cognitive sophistication. Evolution selects for local fitness, not long-term continuity.

At cosmic scale, the same constraint appears as silence. After billions of years and uncountable stars, we see no clear evidence of long-lived, integrated, galaxy-spanning civilizations. This absence does not require universal self-destruction. It is consistent with a universe where intelligence can arise — but struggles to preserve coherence, depth, and identity across deep time.

The pattern repeats not because of shared causes, but because of shared structure.

Continuity as the Real Survival Problem

If this framing is correct, then the central challenge facing any long-lived civilization is not intelligence, nor even alignment in the narrow sense—but continuity.

A surviving civilization is not one that expands fastest or computes most efficiently.

It is one that learns how to remember itself.

Continuity becomes an engineering problem:

- how meaning is preserved across generations,

- how institutions resist decay,

- how knowledge survives catastrophe,

- how values remain legible to the future.

The universe does not select for intelligence.

It selects for systems that can preserve meaning across time.

Whether humanity becomes such a system remains an open question.

The question is not whether the filter exists — but whether we can learn to pass through it.

And that is where we are going next.

Continued Reading & Lineage

This essay situates cognition not as a passive reflector of the world but as an active filter that both enables and constrains what can be known. To extend your engagement with the ideas here — from evolutionary origins of cognition to the structural conditions that shape all intelligible experience — the following works offer deep context and complementary perspectives.

Foundational Thinkers & Books

These texts investigate cognition as an active, world-shaping process — whether through evolution, structure, or interpretation:

- The World as Will and Representation — Arthur Schopenhauer

Early philosophical articulation of how willand representation together shape experiential reality. - How the Mind Works — Steven Pinker

A cognitive science grounding in evolutionary function and modular architecture of the mind. - The User Illusion — Tor Nørretranders

Explores how consciousness is a simplified interface, filtering far more information than it presents. - The Embodied Mind — Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson & Eleanor Rosch

Argues cognition is fundamentally embodied and embedded, not merely computational. - The Perception of the Environment — James J. Gibson

Presents ecological perception as direct, structured by affordances rather than internal models alone.

Sentient Horizons: Conceptual Lineage

This essay draws on and intersects with prior explorations on Sentient Horizons into cognition, time, depth, and systems — especially where they illuminate the shaping role of mind in framing reality:

- Three Axes of Mind — Introduces Availability, Integration, and Depth as structural axes that make cognition possible.

- Assembled Time: Why Long-Form Stories Still Matter in an Age of Fragments — Shows how cognitive depth manifests in narrative as a way of holding extended temporal context.

- Depth Without Agency: Why Civilization Struggles to Act on What It Knows — Applies the axes to societal intelligence and the coordination failures that arise from shallow temporal structures.

- The Shoggoth and the Missing Axis of Depth — Names the absence of depth as a structural quality — and a source of uncanny instability — in artificial cognition.

- Free Will as Assembled Time — Frames agency as the capacity to weave past, present, and future into coherent intentional action.

How to Read This List

If you’re exploring cognition as active, not passive: start with The User Illusion and The Embodied Mind to ground how filtering and embodied structure shape experience. Then read The Universe as a Cognitive Filter alongside Three Axes of Mind to see how structural conditions — like depth and integration — determine what can be known and why.

If you’re interested in broader implications for narrative and systems: pair this essay with Assembled Time and Depth Without Agency to see how cognitive filtering affects not just individual experience, but collective action, cultural narratives, and institutional decision-making.

Taken together, these works illuminate a central insight: cognition is not a mirror but a filtered lens shaped by evolutionary, structural, and temporal constraints — and our sense of “reality” is inseparable from the architecture that makes knowing possible.