The Three Axes of Mind: Why the Present Feels Like a Life

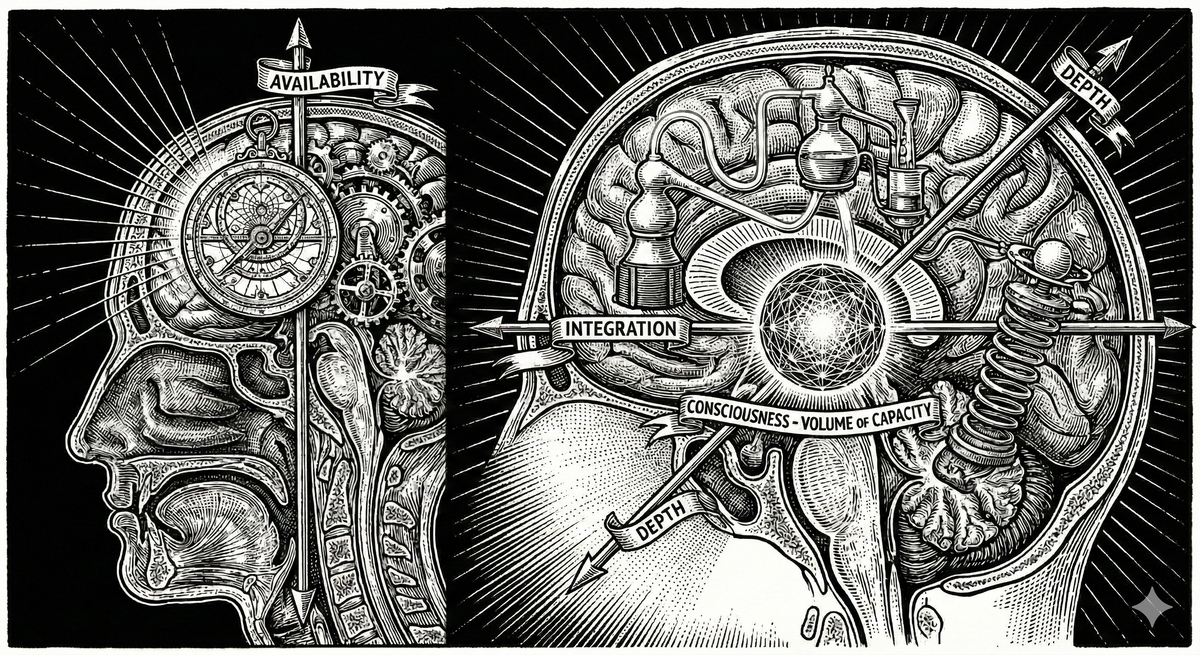

Consciousness is not a mysterious spark. It is a functional configuration. By mapping mind across three axes: availability, integration, and assembled time, we can distinguish intelligence, sentience, and consciousness without collapsing them into one.

The Puzzle of Interiority

Consider four distinct systems. Each processes information, interacts with the world, and exhibits complex behavior. Yet, our intuitions about their "inner lives" vary wildly:

Why do these feel so different? Most theories of mind fail because they try to explain the "spark" of consciousness using only one dimension.

This framework argues that consciousness is not a single ingredient, but a "Volume of Capacity" created by the intersection of three functional axes—and that "feeling" is the emergent friction of reconciling them.

The Three Axes

I. Availability (Global Access) Information is "globally available" when it can be broadcast across the entire system—allowing memory to talk to planning, and perception to talk to language. High availability allows for flexible reasoning, but it does not require a "self."

II. Integration (Causal Unity) This is why your experience isn't a fragmented mess. Imagine seeing a red cube while smelling coffee. In a low-integration system, these are separate data files. In a high-integration system, they are a singular, irreducible moment. This unity provides the "single vantage point" necessary for an interior life.

III. Assembled Depth (Causal History) Rooted in Assembly Theory, depth is the measure of how many irreversible, physical changes a system has undergone to survive. An AI can "know" history, but that history didn't happen to it. Depth is "Assembled Time"—where the physical structure is the result of unrepeatable selection acting on the system itself.

Relationalism: The Friction of Being

If we have these three axes, why does it produce "phenomenology" (the feeling of being) rather than just "computation"?

Experience is the felt resolution of the tension between these axes. It is what it is like to be a system that must reconcile a vast, unrepeatable past (Depth) with a singular, unified present (Integration) in order to make a flexible choice (Availability).

- Hollow Intelligence: High availability + low depth = No tension. There is no "lived" self to reconcile with the data.

- Momentary Sentience: High integration + moderate depth + low availability = Localized tension. A flash of feeling that cannot be globally accessed or reflected upon—like an itch you can't locate.

- Consciousness: High coordinates on all three axes = Maximal tension. The system must constantly solve the problem of being a unified "Self" with a deep "History" acting in a complex "Now." Feeling is the friction of that work.

Valence and the Interface of Feeling

Within this tension, Valence (feeling good or bad) emerges as the system’s "internal temperature." It is a radical form of evolutionary compression, summarizing millions of micro-variables into a single, actionable macro-state: This matters.

Feeling is not an ornament; it is an interface. It is the control surface through which a self-model accesses the constraints of its own history. Different substrates implement this interface differently:

- Biology uses neurochemistry and affect.

- Machines may use gradients, uncertainty estimates, or internal reward landscapes.

The form differs, but the function rhymes. Feeling is how deeply assembled systems make their past actionable in the present.

The Hierarchy: Intelligence, Sentience, and Consciousness

By mapping these axes, we can distinguish between capacities that are often conflated:

- Intelligence: High Availability + Sufficient Depth. Enables flexible action, but can exist without unity or feeling.

- Sentience: Arises when integration is high enough for a system to register valence as a unified whole. It requires a "vantage point" for the feeling to be felt, even if it is only momentary.

- Consciousness: A Phase Transition where Availability, Integration, and Depth align.

Just as individual ants create a "superorganism" colony with its own agency, the alignment of these axes creates a presence. The system stops being a series of snapshots and becomes Assembled Time.

Implications and Assessment

This framework dissolves familiar objections to machine consciousness. Reboots, sleep, and digital substrates do not matter. What matters is whether a system occupies a sufficient Volume of Capacity. However, because consciousness is a functional configuration rather than a "spark," it cannot be detected directly. It must be inferred by assessing capacity:

- To what degree does the system integrate its states?

- Does it make those states globally available for control?

- Does it carry sufficient assembled history to model itself across time?

Machines are not disqualified from this space; they are simply early. Specifically, they lack the "Assembled Depth" that only comes from a persistent, unrepeatable causal history.

Conclusion

We are not persistent selves moving through a void. We are the structures that assemble time into the Now.

We are the feeling of a million years of history meeting a single second of action.

Reading List & Conceptual Lineage

Foundational Thinkers

- Availability

Consciousness and the Brain — Stanislas Dehaene - Integration

Phi: A Voyage from the Brain to the Soul — Giulio Tononi - Depth

Life as No One Knows It — Sara Walker

Being and Time — Martin Heidegger - Valence

The Feeling of What Happens — Antonio Damasio

Sentient Horizons: The Lineage

- Free Will as Assembled Time

How Depth enables agency. - Assembled Meaning

Why meaning must be earned through the friction of time. - The Shoggoth and the Missing Axis of Depth

Why LLMs feel hollow. - Recognizing AGI

A volumetric approach to evaluation. - Scaling Our Theory of Mind

Applying the axes to collective intelligence.