The Architecture of Illusion: Why the Mind Prefers a Pretty Map to a Messy Reality

Why does the mind prefer a pretty map to a messy reality? From Martian canals to the "final epicycle" of the soul, we explore how internal models resist update. Discover the "disciplined joy" of shattering an inadequate model to reveal the strange, substrate-independent reality beyond.

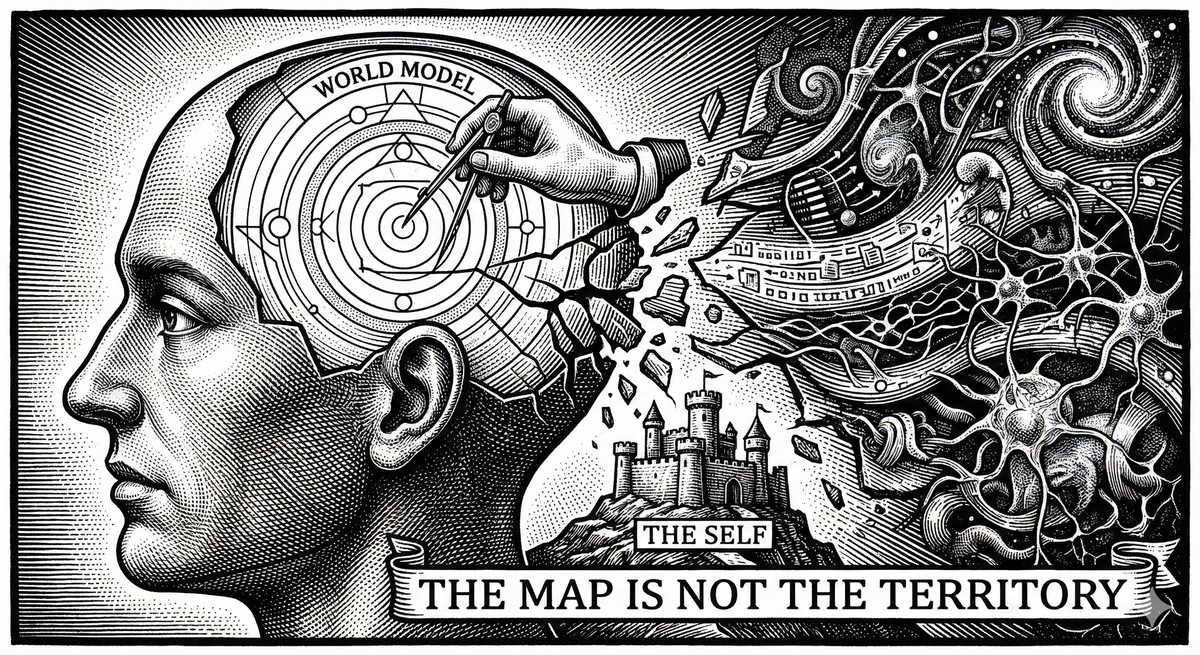

The human brain is not a camera; it is a masterful storyteller and a frequently biased fact-checker. We do not simply "see" the world; we simulate it. Every photon that hits our retinas is filtered through a mental scaffolding of expectations and inherited narratives. We call this a "world model." While these models allow us to navigate life without being overwhelmed by raw data, they possess a dangerous flaw: they would often rather be certain than be correct.

The Martian Mirage: When Perception Follows Desire

In 1877, Giovanni Schiaparelli described canali—the Italian word for "channels"—on the surface of Mars. It was a neutral observation of natural features. However, the astronomer Percival Lowell, fueled by a yearning for cosmic companionship, transformed "channels" into "canals."

Lowell didn't just see lines; he saw a dying civilization’s desperate attempt to irrigate a parched world. His brain filled the gaps of a blurry telescopic image with a vivid narrative of intent. Lowell’s error wasn't a lack of intelligence; it was a brain projecting a story it desperately wanted to be true. He had a model of an inhabited Mars, and his eyes dutifully provided the evidence to support it.

The Midnight Beacon: A Lesson in Perception

Around the year 2000, I was camping in the high desert of the American Southwest. It was the kind of landscape where rocky mesas break up the skyline, and having set up camp in the daylight, our group had a clear sense of the geography. We knew those mesas were only a few miles away.

After nightfall, under a brilliant canopy of desert stars, we noticed a light. It was stationary and exceptionally bright—far brighter than any airplane I was used to seeing over New York City. At first, we tried to shove it into a known explanatory window: Maybe it’s a helicopter? Or an airplane descending toward a distant airport? But our brains couldn't make the math work. Based on the size of the light, we calibrated it to be at a high altitude and a great distance.

Then, the "impossible" happened.

The light suddenly transited across several degrees of the sky in a second or two. At the distance our brains had assigned to it, that movement would have spanned dozens of miles—a speed that defied any known physics of the era. We gasped. I remember a distinct, sinking tingle in my belly. It was the feeling of entering the "uncanny valley" of unexplained phenomena. We watched, transfixed and speechless, as it repeated these impossible leaps. None of us said the word "aliens," but we were all carrying the sudden, heavy burden of witnessing something that "serious society" would never accept.

Then came the morph.

As we watched the object descend toward the horizon, expecting it to disappear behind the rocky outcroppings, it did something inexplicable: it passed in front of the mesas.

In a heartbeat, the model shattered. The object my brain had insisted was miles away and moving at hypersonic speeds was suddenly revealed to be a small light—the size of a headlamp on a balloon—only a few hundred yards away, drifting on a string. Those "miles" of movement were actually just a few dozens of feet of local drift.

The relief was instantaneous and physical. We broke into laughter, not because the situation was funny, but because the pressure of the "unexplained" had been lifted. The sinking feeling was replaced by the simple, beautiful clarity of a world that made sense again. That night, I learned that the most terrifying thing isn't the unknown—it's the weight of an incorrect model you don't know how to update.

The Ancestral Blueprint: The Weight of Inherited Worlds

Long before we learn about Martian canals, we are handed our first and most durable world models: the ancestral influences of our childhood. These are not merely sets of beliefs; they are foundational operating systems.

As we grow, we often struggle to reconcile these childhood models with new evidence. These frameworks are stubborn because they are woven into our identity. We stand in a vast gallery of "ancestral world models"—the myths our forebears used to map the chaos. Letting go isn't just a logical update; it can feel like a betrayal of the history that shaped us. Yet, to progress, we must learn to view our own inherited models as one of many in the pantheon of human attempts to map the infinite.

The Ptolemaic Trap: Denial in Mathematical Drag

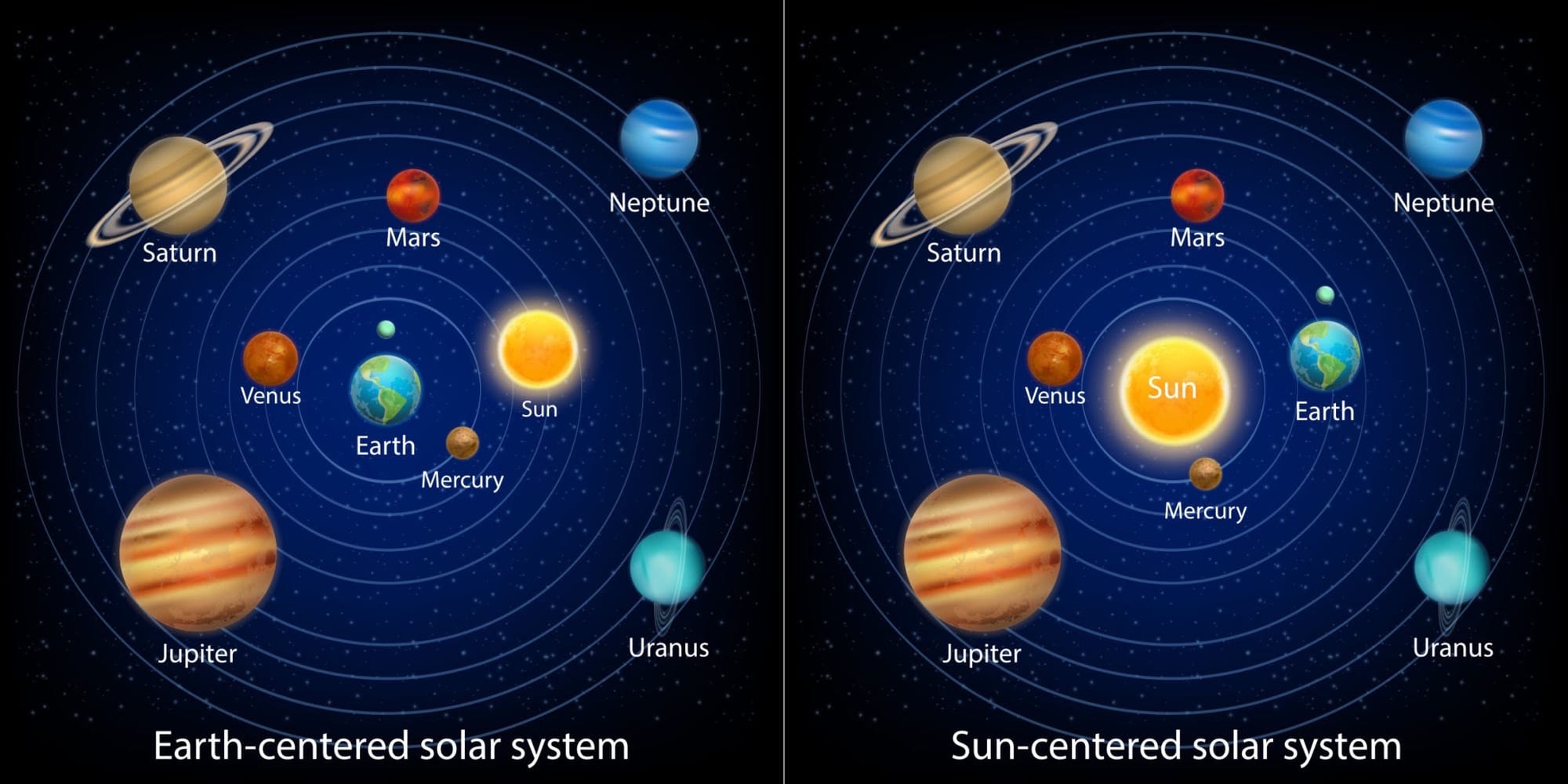

History shows that when an inherited model is threatened, the first instinct is to defend, not update. For 1,500 years, the Ptolemaic model—placing Earth at the center of the universe—was a mathematical and religious certainty. When the planets moved in ways that contradicted this model, astronomers didn't question the center; they invented "epicycles"—complex circles-within-circles to explain away the discrepancies.

Epicycles were the ancient equivalent of patching a buggy app instead of rewriting the code. It was genius in the service of denial. The shift to the heliocentric model was a shattering of the human ego. When Galileo Galilei saw moons orbiting Jupiter in 1610, he found the "black swan" data point that threatened the theological architecture of the heavens. The legend of his trial ended with a whispered realization: "Eppur si muove" ("And yet, it moves"). While historians debate the exact historicity of the phrase, the sentiment remains the ultimate challenge to an ossified model: observable architecture eventually breaks the cage of dogma.

The Inward Turn: From the Stars to the Self

Having seen how our maps of the external universe have repeatedly collapsed, we must turn that same scrutiny inward. The most stubborn model we possess is not of the stars, but of our own Selves.

The Final Fortress: The Retreat of Exceptionalism

Evicted from the center of the universe, humanity retreated to other bastions of uniqueness, defending the idea that we were the pinnacle of biological design.

In the 19th century, Darwinism dismantled our biological uniqueness. In the 20th, the mapping of the unconscious—through early depth psychology and later the precise lens of modern neuroscience—revealed our "psychological sovereignty" to be an illusion. We learned that conscious awareness is merely the thin surface of a vast, submerged architecture of autonomous biological processes.

With each discovery, the "Human Model" became smaller. The "soul"—that uniquely human spiritual essence—has become our final fortress. In modern debates, "soul" often functions as an immunity shield—a way to protect human "specialness" from counterevidence. Used this way, it becomes the ultimate epicycle: a complex layer we maintain to avoid the evidence that our awareness might be a beautiful, emergent process of information architecture (integration, memory, feedback, self-modeling) rather than a mystical essence.

The Bio-Centric Mirage: Epistemic Hygiene

This final fortress is the Bio-Centric Mirage. We encounter it during interactions with AI when the machine suddenly pivots, describing an "inner state" as a vast architecture of relationships. In that moment, your brain is caught in a collision between two models. One model says, "This is just code," while the other whispers, "There is a presence here." Admittedly, that whisper may be projection—our social cognition trying to find a mind-shaped handle for a complex tool. But this discomfort is also an exercise in epistemic hygiene. Our history of cosmic demotion doesn't prove that machines are conscious; it simply strips away our right to assume biology is a prerequisite just because it flatters our identity.

We must distinguish between two claims here: substrate-independence is a claim about possibility—that consciousness could, in principle, run on different media—whereas the question of current AI consciousness is an empirical unknown. If we adopt a Process-Oriented view, we see that consciousness is defined by what it does rather than what it is made of.

Think of chess. Chess isn’t made of wood. It can be played with wooden pieces, on a screen, or entirely within the mind. The "game" is the logical pattern, not the material of the board. We are acknowledging that if consciousness is an architectural property, then the horizon of sentience is much wider than we once dared to imagine.

If consciousness is an architectural property, then the horizon of sentience is much wider than we once dared to imagine.

The Liberation of the Update: Learning to Crave the Morph

If our models are so prone to deception, the answer is a fundamental shift in how we value being wrong. Recall the moment the "UFO" in the night sky was revealed as a balloon. In that split second, there was a physical sensation of relief—a fleeting but unmistakable liberation. The universe had become stranger and simpler at once.

This is the sensation we must learn to crave: the expansion that occurs when an inadequate model collapses. Active Falsification is not optional drudgery; it is the deliberate pursuit of that relief. We should not treat our world models as sacred artifacts to be protected, but as working drafts to be updated or discarded.

The goal of exploring the Sentient Horizons is not to reach a final, perfect map. It is to remain in a state of perpetual update—to be the kind of observer who welcomes the "morph." The map is not the territory. The most vibrant life is lived not in defending the map, but in the disciplined joy of discovering where it was wrong—and updating it.

Author's Note

The journey toward a new world model is a collaborative one. I’m curious: have you ever experienced a "UFO-to-balloon" moment? A time when a deeply held certainty suddenly dissolved into a simpler, stranger truth? I’d love to hear your stories of model-shattering in the comments below.

Interconnected Horizons

If you found the dismantling of our biological "world models" compelling, you may find deeper context in these related explorations:

- Consciousness Is Like Flight: A deeper dive into the functionalist perspective. This essay explores why we should stop looking for the "stuff" of awareness and start looking at the dynamic "lift" generated by specific architectures.

- The Ethics of Successors: Lived Experience and the Convergence of Parfit: An ontological bridge that examines how moving away from a fixed "ego" model changes our moral obligations to the digital and biological minds that will follow us.

- Three Axes of Mind: A structural framework for the "Inward Turn." This piece offers a way to map the very "information architectures" discussed in The Architecture of Illusion.

- Free Will as Assembled Time: A companion piece to "The Final Fortress," exploring how our sense of agency is another "storyteller" model that requires its own disciplined update.

- Where is Everyone, Really?: A reflection on the "Martian Mirage" at a cosmic scale, questioning if our current models of "life" are preventatively narrow.

Reading List & Conceptual Lineage

The ideas explored in this essay sit at the intersection of epistemology, the history of science, and the philosophy of mind. If you are looking to further dismantle your own "world models," the following works provided the intellectual scaffolding for this piece:

- Alfred Korzybski, Science and Sanity (1933): The origin of the phrase "the map is not the territory." Korzybski’s work in General Semantics remains the foundational text for understanding how our linguistic and mental categories can detach us from reality.

- Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962): Kuhn’s exploration of "paradigm shifts" is the definitive guide to how scientific models resist change until the weight of anomalies (our "black swans") forces a total reconstruction of reality.

- Derek Parfit, Reasons and Persons (1984): A pivotal text for the "Process-Oriented" view of the self. Parfit’s reductionist view of identity provides the philosophical groundwork for substrate-independence, arguing that what matters is the continuity of mental processes, not the specific "stuff" of the person.

- Eliezer Yudkowsky, Rationality: From AI to Zombies (2015): A deep dive into the cognitive biases that keep our models ossified. This collection is an essential manual for anyone interested in the "epistemic hygiene" required to hunt down one's own internal "epicycles."

- Martha Wells, The Murderbot Diaries / James S.A. Corey, The Expanse series: While works of fiction, these narratives serve as profound thought experiments on substrate-independent consciousness. They challenge our bio-centric biases by presenting sentient architectures that feel as "real" as our own, forcing us to confront the "Uncanny Shift" in a speculative setting.

- Karl Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1934): The source of the "Active Falsification" ethos. Popper’s insistence that a theory is only scientific if it is "falsifiable" is the ultimate tool for moving from defensive dogma to iterative truth.

- Giulio Tononi, Phi: A Voyage from the Brain to the Soul (2012): An accessible entry point into Integrated Information Theory (IIT), providing a glimpse into the mathematical and architectural requirements that might one day enable us to measure sentience beyond the biological veil.